It’s been five years since we broke ground on the McDonald passive house and it’s time to give this another shot. This time around, it’s going to be different in many ways.

My experience with building structures that use no energy to operate began in the fall of 2016 when we secured a hillside site in the Comox Valley on Vancouver Island. I had done considerable research into passive building and renewable energy over the previous five or so years and embarked on the project flush with what I thought was a good understanding of what I was getting into.

Wrong.

In fact, while I had renovated or fit out a number of homes before, I had little appreciation what a green-field project involved. Site selection and deciding on house plan were the easy bits, all it requires is a compass to locate south and a passive house designer (and I should note there are not many, but their numbers grow every day).

There are many things I underappreciated, but two stand out: the ordeal that is project management, and the concept of embodied carbon.

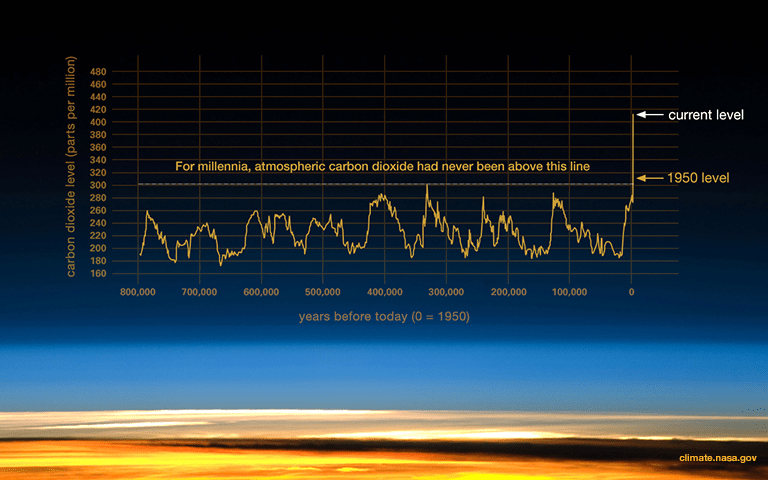

First the latter: embodied carbon is that which is in the materials you use to make any product. We are made of carbon and it occurs in more compounds on the earth than any other element. The four most abundant elements in the human body are hydrogen, oxygen, carbon and nitrogen. The problem we have with carbon in the Anthropocene period is that when it bonds with oxygen to form CO2, it creates a gas we should not have an overabundance of because it warms up the planet. NASA, one of the great generators of cool facts, tells us that there is more CO2 on earth now than in any time in the past 400,000 years. See NASA’s chart above.

Thing is, almost every supply chain and industrial process on earth creates CO2. Given we have too much of it already, we need to minimize it.

House construction using conventional means generates massive amounts of CO2. Two of the biggest offenders are concrete and plastics, both of which require fossil inputs to make. My first passive house has a lot of thermal mass (concrete’s a good one!) and insulation (expanded polystyrene foam, EPS, or styrofoam) are two things that work really well. My basement uses both – it is insulated concrete forms (ICF), which are EPS filled with concrete, and just to add insult to injury has steel (rebar) down the middle of it. All of it works great for energy efficiency and structural strength. All of it is extremely destructive to the planet.

But let’s not throw the baby out with the bath. We need these things, but the question is degree.

Preparing to break ground on passivetom 2.0, the Timberlane project, I have resolved to do the following.

- Find alternatives for concrete in the foundation, but use concrete judiciously and only when necessary

- No polished concrete floors. Great thermal mass, but environmentally unsound. There are alternatives (stay tuned)

- No EPS under the slab (McDonald passive house has a huge amount, I was shocked when the flatbed trailer full of it showed up in June 2017)

- Use laminated timbers, not old growth trees (which sequester carbon)

- Insulate with wood (such as wood fibre board and cellulose, both of which can be made with wood waste or recycled paper)

Now, one can argue that this approach is over the top. Some will say the EPS’s insulating properties will redeem it over the lifecycle of the house. That is true, the energy you don’t use because of the greater insulating value will compensate over time for the fossil material used to make the EPS. But if there are alternatives, why not use them and eliminate all that carbon at the outset? And what about end-of-life for this house? Binding concrete to EPS does not make a recyclable product, full stop.

In future posts we will examine materials that help us cut embodied carbon. There are lots of ideas out there. We will also look at how to cut waste (and thus landfill methane, a very potent greenhouse gas) in the construction process. Anyone setting foot on a construction site will notice the massive dumpsters where everything goes, especially packaging materials for building components. Separate, segregate, reuse where possible, and recycle where not. That’s where we want to go.

Tom.